Scott Gries Getty Images

On May 29, as the nation rioted and marched and demanded justice for George Floyd after his death at police hands, Donald Trump tweeted a callback to the segregationist and Alabama governor George Wallace: “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Two days later the president sought to clear peaceful protesters from the path between the White House and St. John’s Church for a photo opportunity. According to recent reports, federal officials had spent the preceding hours stockpiling ammunition and seeking “devices that could emit deafening sounds and make anyone within range feel as if their skin was on fire,” one of which was described as a “heat ray.” Officers instead opted to use rubber bullets, smoke grenades, and capsaicin-filled pepper balls to clear Lafayette Park.

Outkast’s “B.O.B. (Bombs Over Baghdad)” turned 20 years old last month, and the song feels oddly fitting now, as an analogue for what being Black feels like in 2020.

Outkast was experiencing creative transition 20 years ago, just as America is experiencing social transition today. The duo were trying to blend Big Boi’s street hustler roots and André 3000’s Afro-intellectualism with the American musical marketplace’s pop expectations. Three studio albums into their career, their popularity was growing. 1998’s Aquemini, the duo’s third album, went platinum in two months, but its singles made none of the impact that its predecessor’s did. Although the album featured well-produced, culturally impactful singles like “Rosa Parks,” none of its productions reached the Billboard top 10.

Outkast figured they needed something wildly unpredictable to bridge that gap and regain the ground they had started to control around 1996’s ATLiens. “B.O.B,” the frenetic and sonically shocking lead single from Aquemini’s 2000 follow-up Stankonia, was that something. André 3000’s hook — ”Don’t pull the thang out, unless you plan to bang” — wasn’t a direct reference to the scud and Tomahawk missile-type “bombs over Baghdad” of the Gulf War of 1990-91. Nor was the term a direct criticism of US attempts to “degrade” Iraq’s ability to produce weapons of mass destruction during Operation Desert Fox in 1998. Still, soldiers looking for a lyric to keep them motivated during the 2003 Iraq War ham-handedly appropriated the lyric as a rallying cry of their own volition.

In reality, the term’s roots lie deep within the street-corner slang tradition of Black urban communities. Euphemistically, “pulling your thang out” to “bang that thang” is 1970s Blaxploitation slang for shooting a gun or a man reaching orgasm while having sex. Much of Outkast’s inspiration and imagery has kinship with George Clinton, Parliament-Funkadelic, and Dolemite dipped in brown acid.

It’s not just me that feels this way. A 2000 Village Voice review of Stankonia is entitled “Make My Crunk The P-Funk” — despite not mentioning that Stankonia could easily be, as Clinton says on 1975’s “P Funk (Wants To Get Funked Up),” the “home of the extraterrestrial brothers, dealers of funky music, P-funk, uncut funk, the bomb.” Watching Dolemite, “Joe Blow, the lover man” seems like he’s a second away from stating that he wants to “pull his thang out to bang that thang” before being assaulted for underpaying a sex worker.

Until I realized that it was happening in real life, the footage of protestors being forced from Lafayette Park felt like some sort of absurdly grim revenge-style reenactment of Rudy Ray Moore as Dolemite, being chop-socked and karate-kicked by the “rat-soup-eatin’ honky motherfuckers” infringing on his rights.

On the evening of Trump’s photo-op I went for a run with my headphones in, and the algorithm spat out “B.O.B.” after a playlist I’d compiled had ended. The terrifying pseudo-reality smacked me in the face. A headache-inducing surge of stress assaulted my temples as the Morris Brown College Choir cried for a “power music, electric revival” over the 155 BPM drum-and-bass-style production by Earthtone III, the name of Andre, Big Boi, and Outkast DJ Mr. DJ’s production collective. “Thoughts at a thousand miles per hour,” Andre rifled off.

Closing my eyes from the stress, my imagination exploded. An enraged population of Americans sprinted, unrestrained, like a herd of “elephants and silverback orangutans.” The skyline turned a dramatic cerulean blue, and the landscape a stunning shade of violet. Had I not remembered the song’s music video, it would’ve looked nothing like anything I’d ever seen before.

The way my body processes and responds to the summer of 2020 in this racial violence-ravaged America feels — to borrow from “B.O.B.” reviews in The Village Voice and Yahoo! Music — like equal parts an “electro praise-and-worship service” and an “[explosion of] revved-up adrenaline.”

Running uphill, at a 30-degree incline, with my heartbeat pulsing in my ears alongside “B.O.B.,” in a section of suburbs cut into the woods of Glen Echo Park, was already a mind-splitting task. Now, with this psychedelic landscape in front of me, I was “hitting somersaults without the net, sittin’ in a drop-top, soakin’ wet, [while] in a silk suit, tryin’ not to sweat.”

As I reached the top of the hill, I realized that I had to run twice as far downhill along the same path. The state of mind-blown and funkdafied zombification that set in made me feel as though I was stuck in suspended animation-as-hopelessness. This hopelessness was a fraction of the exhaustion that folks must’ve felt in Lafayette Park when realizing, frustrated and tired, that violent unrest was the only remedy that remained.

When Rolling Stone asked Three Stacks in 2003 why “B.O.B” made sense to soldiers in Iraq at the time, he gave an answer that helps to put the immediacy of the present moment for so many Black Americans into starker relief. “The U.S. was trying to beat around the bush,” he said of the first Gulf War. “We was trying to scare them by bombing the outskirts. If you’re going to do anything at all, do it. If you gonna push it, push it.”

Well, we’re pushing it now.

André was just as potent six years later, telling Blender that Outkast insisted on releasing “B.O.B” as the album’s first single before surefire radio hit “Ms. Jackson,” despite their label’s wishes. “You could come off the Aquemini album, like, calmed down, or just turn it up to notch 20,” he told Jon Caramanica. Outkast wanted to set the tone with “notch 20.”

In my mind, whenever I hear Andre’s rap “Hello, ghetto, let your brain breathe,” it feels as though he’s describing the perfect moment to rest at “notch 20” and handle what we can, as best we can. In 2020, amidst what feels like a never-ending series of apocalyptic-style threats against my existence, that feels right.

Black Americans are turned up, but our now breathing brains exist at a time when there’s so many questions, no answers. Everything’s as wrong as it has ever been. “If you gonna push it, push it.” Our thoughts at a thousand miles per hour, we’ve breathed, and we’re past the point of being afraid to bang.

Listening to Outkast’s “Bombs Over Baghdad” while America explodes

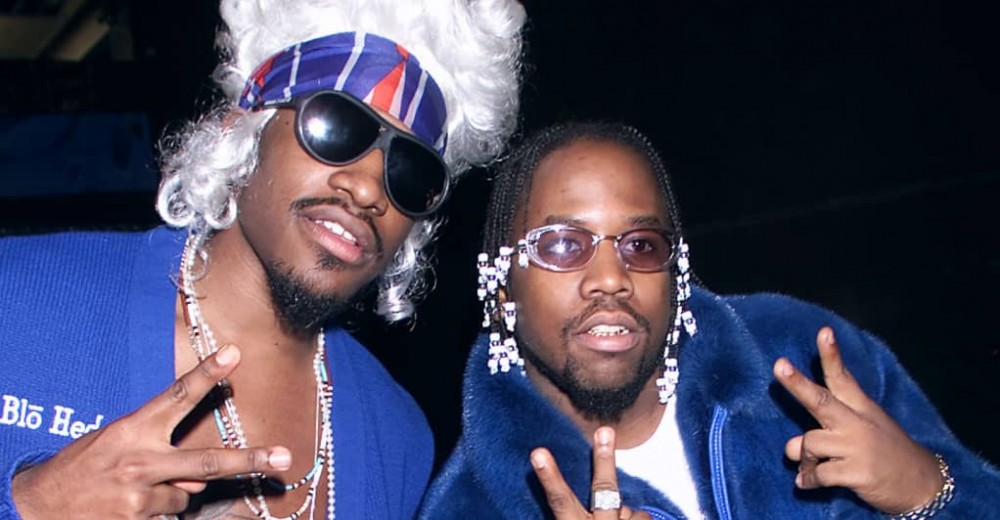

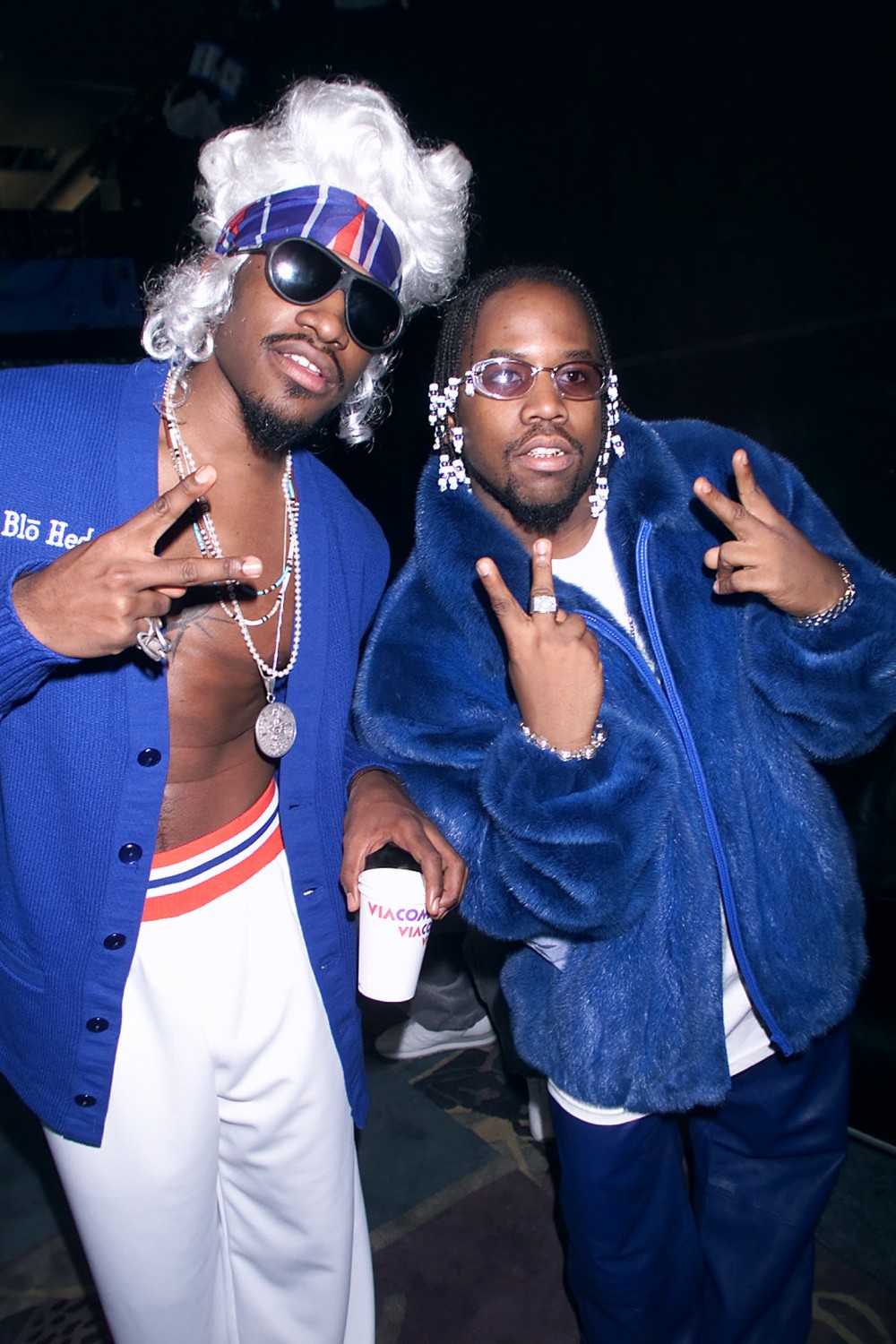

Outkast in 2000, the year of “B.O.B.”‘s release.

/